Introduction

Clustering methods attempt to group object based on the similarities of the objects. For example, one can group their customers into several clusters so that one can aim a specific way of marketing to each type of customers.

Since there is no preexisting group labels for each cluster, we can never know the accuracy of clustering methods unless using a simulated data.

There are some complexities in clusterings:

- What is the number of clusters? We have no way to validate the results so we can’t even use cross-validation to choose one. Perhaps, using domain knowledge is the best way to validate the results. We will use the Elbow Method to decide the here.

- How do we define similar? In other words, what is the similarity measure? Clustering results depend heavily on the measure of similarity. Some of the famous measures between two data points are:

- Pearson correlation between two points

- Distance between two points

- Number of matches between two points (i.e., having the same category)

I am using the Distance, the Euclidean distance to be specific, as the similarity measure in this post.

The Problem

Let’s say we have data vectors and we have vector clusters with cluster centers of . We want to minimize the following error:

In other words, given a fixed number of cluster, , we want to mimimize within cluster dissimilarity. This is calculated by taking the difference between each data points from its cluster centroid (the center, ), which also has dimensions. This also means that we cluster the data points to the closest centroids from them.

However, finding that minimizes is NP-hard (as hard as nondeterministic polynomial time problem). It is not feasible to find: because we have to minimize over all possible assignments of points to clusters. The number of distinct assignments is:

K-means Clustering

The Lloyd’s algorithm turns out to be the most famous iterative algorithm used to attempt minimizing the objective function.

The algorithm is simple:

- Partition the objects into initial clusters .

- Do the following:

- Assign object to cluster that has the closest centroid(mean). Repeat this for .

- Update the cluster centroids by taking the sample mean within each cluster.

- Repeat 2 until no changes in cluster assignment is observed (means it has converged).

Implementation

mykmeans <- function (data, k, centers = NULL, stop_crit = 10e-3, seed = 1001)

{

# Initializations

set.seed(seed)

# Assigning the initial centroids. Random value will be used

# if no values were specified

if(is.null(centers)) centers = sample.int(nrow(data), k)

centroid <- data[centers, ]

# Keep a history of the centroid values for visualization purpose

cen_hist = data.frame(centroid)

# Randomly assign clusters to each observations

cluster <- c(sample.int(k, nrow(data), replace = TRUE))

# Keep a histpry of the data frame that includes assigned clusters

# for visualization purpose

data_hist <- data.frame(data,cluster)

# Within group Sum of squares

withinss = c()

# size of each cluster

size = c()

# Does it converge?

conver <- F

# distance between old and updated centroids

# Set it as arbitarily large

dist_crit = 10e5

# Number of iteration

iter = 1

while (conver == FALSE)

{

old_centroid = centroid

# assign to cluster that has the closest centroid to a specific data point

for (i in 1 : nrow(data))

{

dist = apply(centroid, 1, function(x) sum((x - data[i,])^2))

cluster[i] = which.min(dist)

}

# Update the centroid mean

for (j in 1 : k)

{

centroid[j, ] = apply(data[cluster == j, ], 2, mean)

}

## Keep the history of the centroid and data + cluster

cen_hist = rbind(cen_hist, data.frame(centroid))

data_hist = rbind(data_hist, data.frame(data,cluster))

# Is the stopping criteria met?

dist_crit = mean((old_centroid - centroid)^2)

if (dist_crit <= stop_crit) conver = TRUE

# Update iteration

iter = iter + 1

}

#### Sum of squares calculations#####

for (m in 1 : k)

{

withinss[m] = sum((apply(data[cluster == m, ],1,

function(x) x - apply(data[cluster == m, ],2,mean)))^2)

size [m] = sum(cluster == m)

}

totss = sum(apply(data, 1, function(x) sum((x - apply(data,2,mean))^2)))

tot.withinss = sum(withinss)

return(list(data = data.frame(data,cluster),

cluster = cluster,

centroid = centroid,

totss = totss,

withinss = withinss,

tot.withinss = tot.withinss,

betweenss = totss - tot.withinss,

size = size,

cen_hist = cen_hist,

data_hist = data_hist,

iterations = iter))

}Data Simulation and Visualization

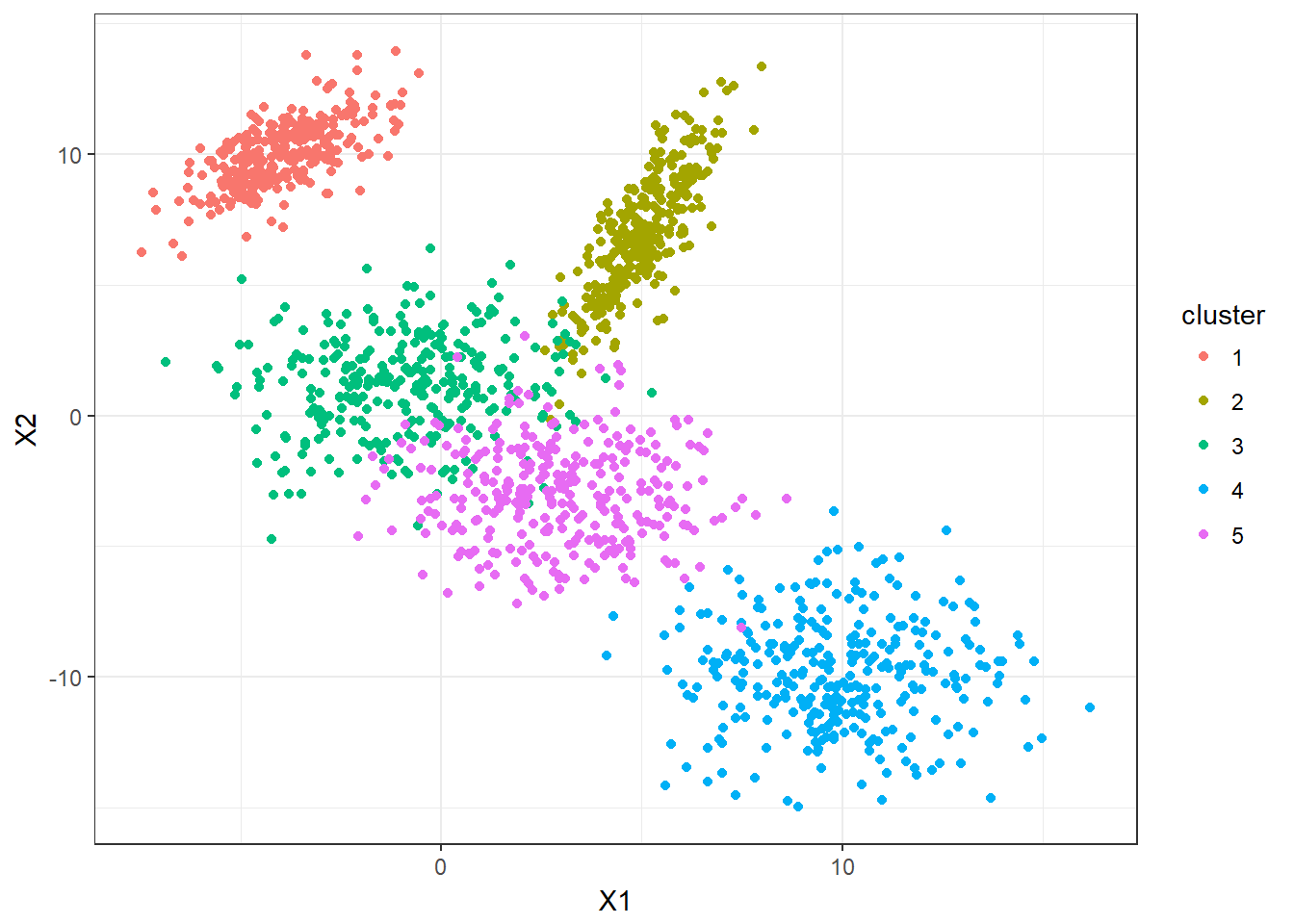

The following simulation is adapted from http://enhancedatascience.com/2017/10/24/machine-learning-explained-kmeans/ .

5 clusters with 300 observarions each are simulated. Let’s take a look.

require(MASS)

require(ggplot2)

set.seed(1234)

set1=mvrnorm(n = 300, c(-4,10), matrix(c(1.5,1,1,1.5),2))

set2=mvrnorm(n = 300, c(5,7), matrix(c(1,2,2,6),2))

set3=mvrnorm(n = 300, c(-1,1), matrix(c(4,0,0,4),2))

set4=mvrnorm(n = 300, c(10,-10), matrix(c(4,0,0,4),2))

set5=mvrnorm(n = 300, c(3,-3), matrix(c(4,0,0,4),2))

DF=data.frame(rbind(set1,set2,set3,set4,set5),cluster=as.factor(c(rep(1:5,each=300))))

ggplot(DF,aes(x=X1,y=X2,color=cluster))+geom_point()

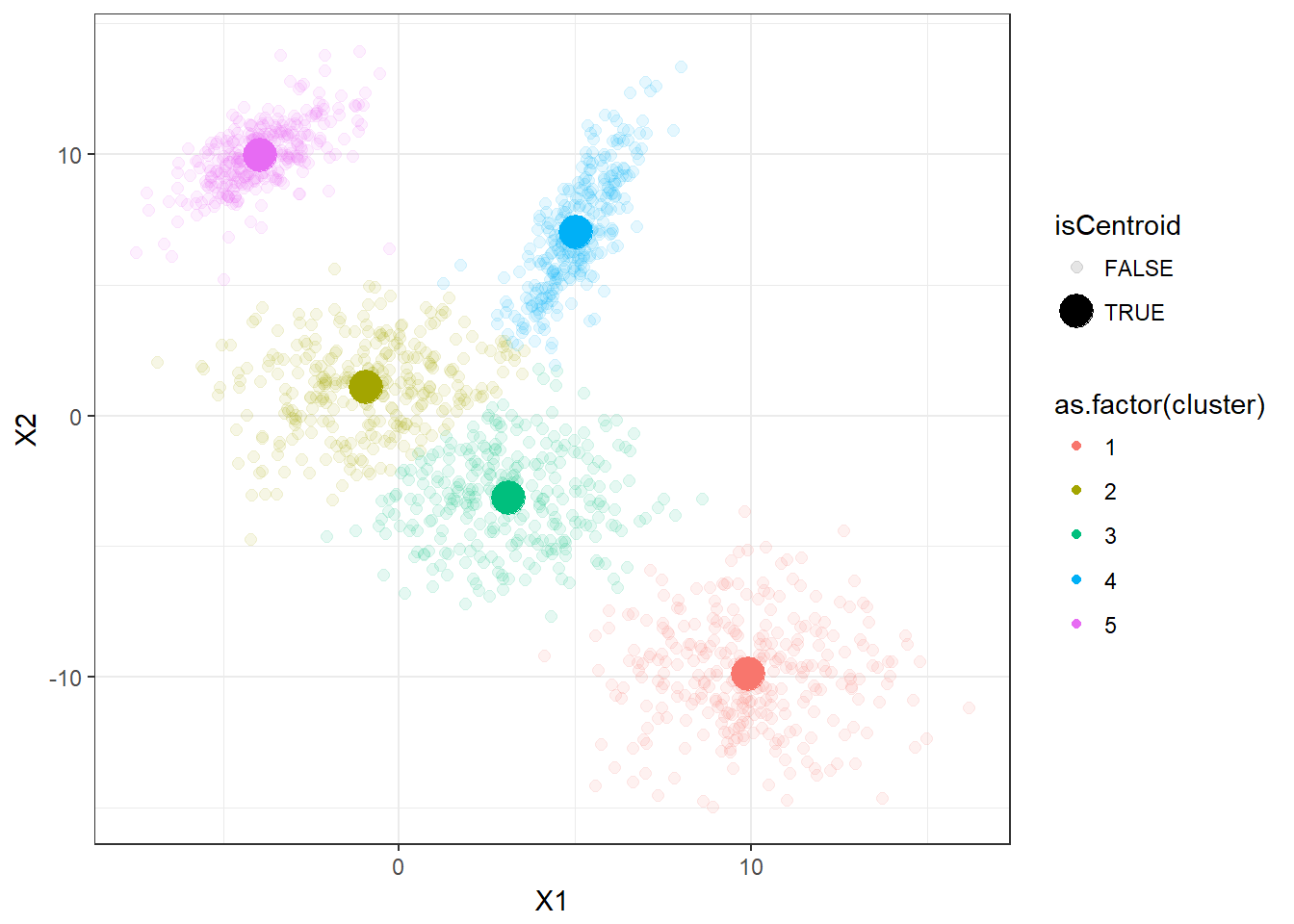

Now, let’s apply the K-means clustering function that we just defined. We can also visualize how K-means is performing in this dataset.

k = 5

res=mykmeans(DF[1:2],k=k)

res$centroid$cluster=1:k

res$data$isCentroid=F

res$centroid$isCentroid=T

data_plot2=rbind(res$centroid,res$data)

ggplot(data_plot2,aes(x=X1,y=X2,color=as.factor(cluster),

size=isCentroid,alpha=isCentroid)) +

geom_point()

It appears that the K-means clustering is working well here since the 5 clusters are separated correctly.

Let’s look at how the K-means algorithm is working in the following visualization. We can see how the centroid is moving and form the 5 clusters correctly.

K-means ++ Clustering

The problem with k-means clustering is that it only provide local minimum but not global minimum. In other words, where you set as the inital centroids plays a big role. Thus, the usual method is to use different initial values, look for the stable solution (clusters) and choose the best initial value from there.

In 2007, David Arthur and Sergei Vassilvitskii introduced k-means++.

The big idea is that instead of choosing centroids randomly, it’s better to choose the centroids such that they are far from each other. The major advantage of this approach is that we don’t have to try several initial values. This cuts down the computational time a lot.

The following is the algorithm of choosing the initial centroids:

- Denote a randomly chosen point as .

- For the th iteration, , compute the squared distances, : . The probability that is chosen as the centroid, , is with and .

- Repeat this until we collect .

- Use the collected points as the staring centroids for k-means algorithm.

Implementations

kmeanplus <- function(data, k, ...)

{

n = nrow(data)

# Place holder

centroids <- rep(NA, k)

dist <- matrix(nrow = n, ncol = k-1)

# Initialize probability = 1 for all data points

probs = rep(1, n)

for (i in 1: (k-1))

{

# The s_k

centroids[i] = sample.int(n, 1, prob = probs)

# The D_i^2

dist[,i] = (apply(data, 1, function(x) sum((x- data[centroids[i], ])^2)))

# Not counting the exact probabily here. All we care is the relative weight.

probs = apply(dist, 1, function(y) y[which.min(y)])

}

centroids[k] = sample.int(n, 1, prob = probs)

res <- mykmeans(data = data, centers = centroids, k = k, ...)

return(res)

}Visualization

Let’s reuse the same dataset as above and visualize the clustering process.

res <- kmeanplus(DF[1:2], k = 5)

The number of iterations is 7 this time.

Choosing K - the Elbow Method

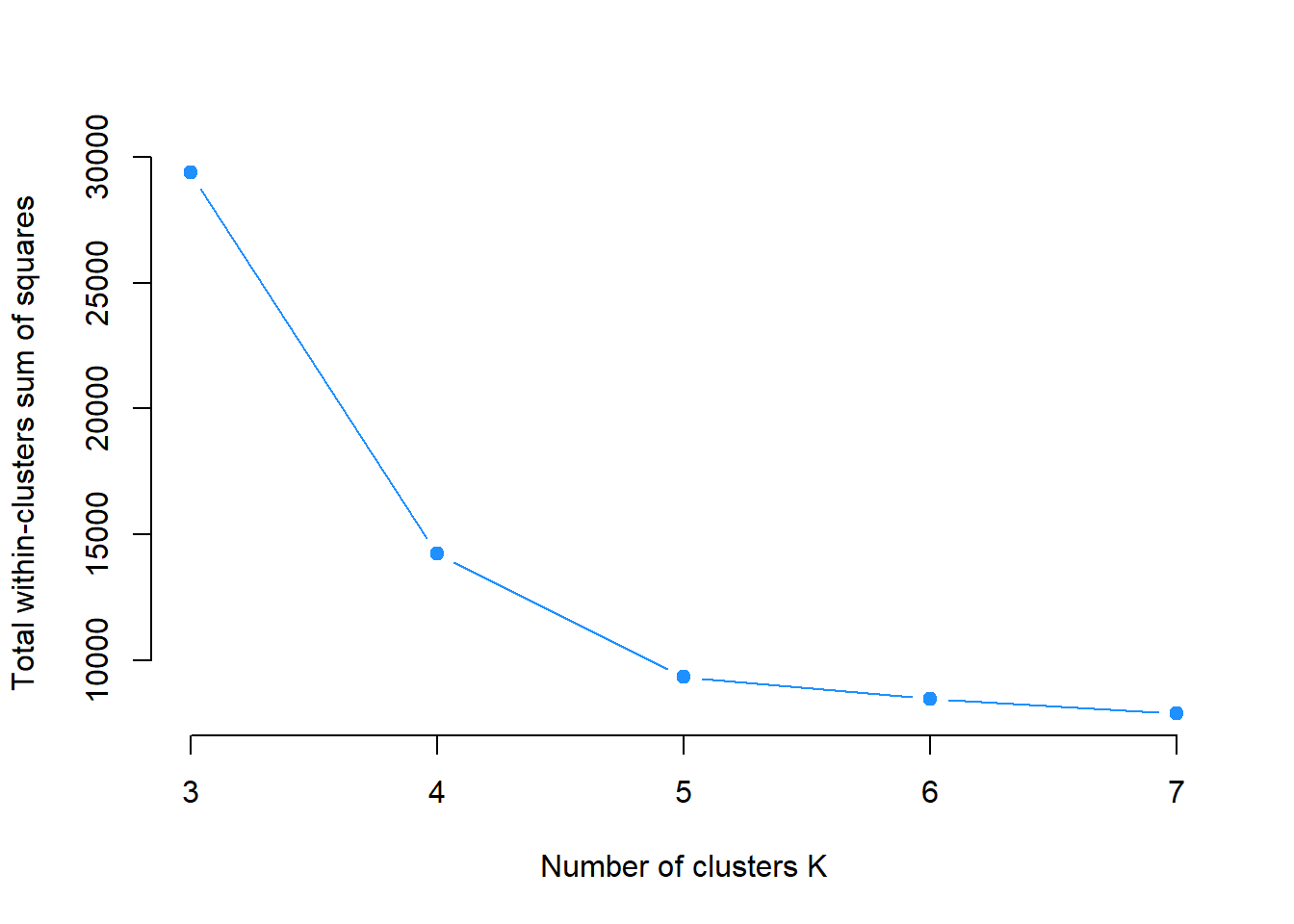

The Elbow Method will be used in this case. Recall that all we were doing is to minimize the within cluster sum of squares. We can vary the value of , say from 3 to 7, and plot the within sum of squares against the s. The location of a bend in the plot can be considered as the optimal because it means that further increasing number of is not decreasing the within sum of squares a lot.

set.seed(1001)

# Compute and plot wss for k = 3 to k = 7

k.values <-3:7

wss = c()

for (k in k.values)

{

wss = c(wss, kmeanplus(DF[1:2], k = k)$tot.withinss)

}

plot(k.values, wss,

type="b", pch = 19, frame = FALSE,

xlab="Number of clusters K",

ylab="Total within-clusters sum of squares",

col = "dodgerblue")

The Elbow is seen at and that is congruent with our simulated 5 clusters.

Next Step

There are different ways of choosing the number of clusters in adddition to the Elbow method. One can also try on more data simulations and discover the limitations of k-means clustering.